For the past five years, the Palma Futuro project has built up robust social performance systems to improve conditions for workers at every level of the palm oil supply chain in Colombia and Ecuador through engagement inside and outside of the workplace.

We spoke with Yolanda Brenes Hernandez, Palma Futuro’s Lead Trainer and Senior Manager of Latin America Programs at SAI. Yolanda tells us about her experience working with palm oil producers and extractor plants in Ecuador and Colombia, the impact of the project, and SAI’s work in Latin America.

What was your role in the Palma Futuro project?

As the lead trainer, my role has involved liaising with, providing technical assistance to, and training Palma Futuro’s private sector partners (palm oil extractor plants and producers) in Colombia and Ecuador. I also coordinated with other stakeholders, such as Ministries of Labor, unions and sector associations, in these countries as well as in Peru, where we disseminated learnings from the project.

Why do you think Palma Futuro’s mission was important for the palm oil industry in Colombia and Ecuador?

I think it is different for each country and partner. For the palm oil extractor plants, the challenge was to deepen the existing knowledge of labor rights and human rights. Before working with Palma Futuro, much of the management at these companies spoke only in the language of certification and compliance, without a complete understanding of the importance of labor rights and how to ensure them for their workers.

For the palm oil producers, it was a different challenge. We found that many producers often understood labor performance from the perspective of obligation, rather than something that benefits their community members and their own business. We introduced the importance of addressing human rights issues in operations of any size, as the majority of producers we worked with were small to medium-sized. For example, the formalization of workers on the farms was and continues to be a very important challenge for palm oil producers, because there is a general fear of formalization that is often due to a lack of knowledge about its long-term benefits. It was very gratifying to see producers and their workers come to understand the implications that formalization has on their wellbeing by providing benefits for themselves and their families (such as social security and pension plans).

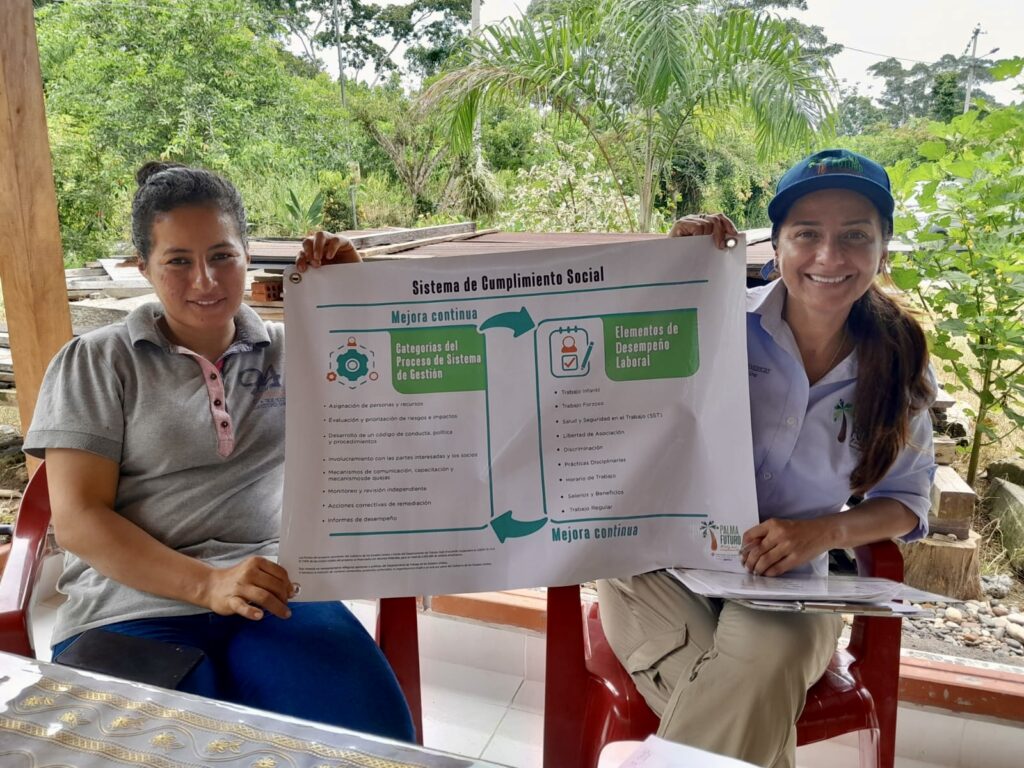

Photo provided by Palma Futuro project, funded by the United States Department of Labor (USDOL)

Now that the project has finished, how have you seen its impact?

For all our partners, the Palma Futuro trainings, technical assistance, and tools provided a great deal of knowledge and learning about human rights. It was wonderful to see how they deepened their commitment to labor rights and promoted worker voices by creating spaces for them to share their suggestions, ideas, and concerns. I was glad to see that by the end of the project, some companies had incorporated a new human rights training component into their onboarding processes for new employees – using the human rights concepts, games, and tools from our Palma Futuro trainings.

It was also great to see how our trainings enhanced the understanding of due diligence for our private sector partners. For example, we found that prior to working with Palma Futuro, partners often had policies on certain issues, such as discrimination, but were not always following up on the implementation of those policies. For example, there were some operative workers at an extraction plant who expressed that they felt discriminated against during workday mealtimes, because they were required to eat in a cafeteria separate from the administrative staff. When confronted with this issue, management expressed surprise, telling us that they had never thought about this through the lens of discrimination, despite their existing policy. They went on to re-write this policy and tore down the original cafeterias to build a new and improved cafeteria for both operative workers and administrative staff to utilize at the same time.

Another improvement that I saw at extractor plants was how companies’ processes changed from being reactive to certification requirements to preventative through the incorporation of social compliance systems. By learning to identify labor risks across all areas (rather than just Health and Safety, which was previously where many companies focused their attention), they were able to proactively find issues in other areas.

Additionally, the Training of Trainers program was a great strategy for the sustainability of Palma Futuro’s work. Now that the project has finished, the trainers that completed the program are prepared to continue capacity building inside the companies, as well as monitoring and helping producer farms implement their own social compliance systems.

Was there a moment during your work with Palma Futuro that you found particularly impactful?

There was one extractor plant that already had a complaint and suggestion system before working with us but told us that workers never used it. After completing Palma Futuro trainings, they realized that they were not effectively promoting the complaint channel and ensuring that workers understand how to use it. To address this, they implemented changes in their internal trainings, protocols and approach to communication (including creating infographics on proper usage) about the grievance mechanism system. It was very exciting to hear the management of this extractor plant say that after years of having their complaint system, they now finally understood how to correctly implement it.

Afterward, they told us that they had started receiving feedback from workers who were raising important issues about the company’s health and safety, canteens, and more. Implementing these changes to their processes has given workers the confidence to use the complaints and suggestions mechanism and also has resulted in necessary improvements that management had not detected before.

How did you first become involved in SAI’s work and what is your role now?

This story begins in 1999 when I was corporate responsibility manager for Chiquita Brand Corporativo in Costa Rica, and we started the process of broadening our environmental concept of corporate responsibility to go deeper into labor issues. The company decided to use the SA8000 Standard to certify all banana production operations in Latin America, which is how I first learned about SAI and the SA8000 Standard.

After we certified more and more farms, I became very familiar with the SAI trainers and their methodology. I began working as a consultant for SAI and SA8000 trainer in Latin America in 2007, and now as of this year, I am the Senior Manager for Programs in Latin America at SAI.

How have you seen labor rights and social compliance issues change since you started working in this field?

While there are important challenges that remain (such as issues facing vulnerable populations), the way that labor rights issues are understood and addressed has advanced quite a bit over the years. As international regulations and legal standards have developed to help us monitor compliance with labor rights, we have seen an increased commitment from corporations and in their supply chains. Importantly, we have also seen a shift towards utilizing comprehensive management systems that emphasize stakeholder engagement – rather than approaching situations with very specific one-time solutions. By using this approach, labor rights issues can be mitigated much more quickly than they were in the past, and systems are built to prevent and monitor future risks.

Looking ahead, what are you excited about for SAI’s work in Latin America?

What excites me about human rights and social compliance work in Latin America is the possibility of contributing to building more just and inclusive societies. In this region, there are significant human rights challenges, but also great potential for positive change. I am excited to be able to collaborate in the protection of people’s rights and the promotion of sustainable development that benefits all of society. It is exciting work and full of opportunities to make a positive impact!

Funding is provided by the United States Department of Labor under cooperative agreement number IL-32820-18-75-K. 100 percent of the total costs of the project is financed with federal funds, for a total of 6,000,000 US dollars. This material does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the United States Department of Labor, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the United States Government.